Quick Links

Use the quick links below to find the resources and information you need to implement and maintain Safety IQ in your pharmacy.

Analyze and Act

There are two types of analysis required in the Safety IQ program: proactive and reactive analysis.

Proactive analysis begins with a safety self-assessment (SSA). Pharmacy teams use an SSA to proactively analyze their systems and processes to identify areas of risk in their practice. Findings from the SSA are then used to develop an improvement plan to reduce risky practices and close any patient-safety gaps. For more information about SSAs, please visit the following link: http://safetyiq.academy/safety-self-assessment/

Reactive analysis is triggered when a medication incident harms a patient or a pattern of similar incidents or near-miss events emerges. The pharmacy team should immediately examine the incident, identify root causes, and openly discuss the incident with all staff. An improvement plan is then developed and implemented with the input of your team.

Understanding a problem is the key to its solution; however, we often jump too quickly from problem to solution without seeking a true understanding of its root cause(s). Sometimes we think we have found the cause of problem, but we are actually just examining a symptom.

There are many approaches to incident analysis, but the most important thing is to choose an approach that is right for your team. The suggested processes below are examples of simple methods you could use with your team to analyze medication incidents or patterns.

Analysis Resources

Adapted from the Institute for Health Improvement’s (IHI) Quality Improvement Essentials Toolkit.

Step One: Gather all the information you have about the incident or data trends you are examining. This may include an incident report, staff interview, or aggregate data reports.

Step Two: Conduct an analysis of the incident or data trend to discover root causes using ‘5 Whys’ and ‘Fishbone Diagramming.

Step Three: Develop and document an improvement plan that reduces or eliminates the root causes you identified in your analysis.

Step Four: Use ‘Plan, Do, Study, Act’ (PDSA) cycle to study your changes and ensure they are effective and haven’t introduced the root causes of a future medication incident.

One way to identify the root cause of a problem is to ask “Why?” five times. When a problem presents itself, ask “Why did this happen?” Then, don’t stop at the answer to this first question. Ask “Why?” again and again until you reach the root cause.

This simple tool can be surprisingly insightful in helping you figure out what is really going on and can help you avoid quick fixes. It is especially useful for tackling chronic problems that show up over and over again in a complex system.

It’s important to note that there may be multiple root causes of a problem, and that different people who see different parts of the system may answer the questions differently.

Use the following steps to conduct a simple analysis of a medication incident or near-miss event. A ‘5 Whys’ worksheet is available through IHI’s Patient Safety Essentials Toolkit.

Step One: Define the problem or event – be clear and specific.

Step Two: The facilitator asks why the problem happened and records the team response. The facilitator asks the team to consider, “if the most recent response were corrected, is it likely the problem would recur?” If the answer is yes, it is likely this is a contributing factor, not a root cause

Step Three: If the answer provided is a contributing factor to the problem, the team keeps asking “Why?” until there is agreement from the team that the root cause has been identified.

Step Four: It often takes three to five whys, but it can take more than five! The team continues to ask “Why” until the team agrees the root cause has been identified.

Step Five: Explore the best way to solve the problem, develop an improvement plan, and make changes to the system to prevent recurrence.

The 5 Whys is a simplified process and, in many cases, may require further analysis such as using a Fishbone Diagram Analysis described in the next tab on this webpage.

Fishbone Diagram Process

Step One: Agree on the problem statement and write it at the mouth of the “fish.” Be as clear and specific as you can about the problem. Beware of defining the problem in terms of a solution (e.g., we need more of something).

Step Two: Agree on the major categories of causes of the problem. Major categories can include: technology/ equipment factors, environmental factors, organizational factors, policy/procedure factors and people/staff factors. Choose any useful category.

Step Three: Brainstorm all the possible causes of the problem. Ask “Why does this happen?” As each idea is given, the team leader writes the causal factor as a branch from the appropriate category. Causes can be written in several places if they relate to several categories.

Step Four: Again ask, “Why does this happen?” about each cause. Write sub-causes branching off the cause branches.

Step Five: Continues to ask “Why?” and generate deeper levels of causes and continue organizing them under related causes or categories. This will help you to identify and then address root causes to prevent future problems.

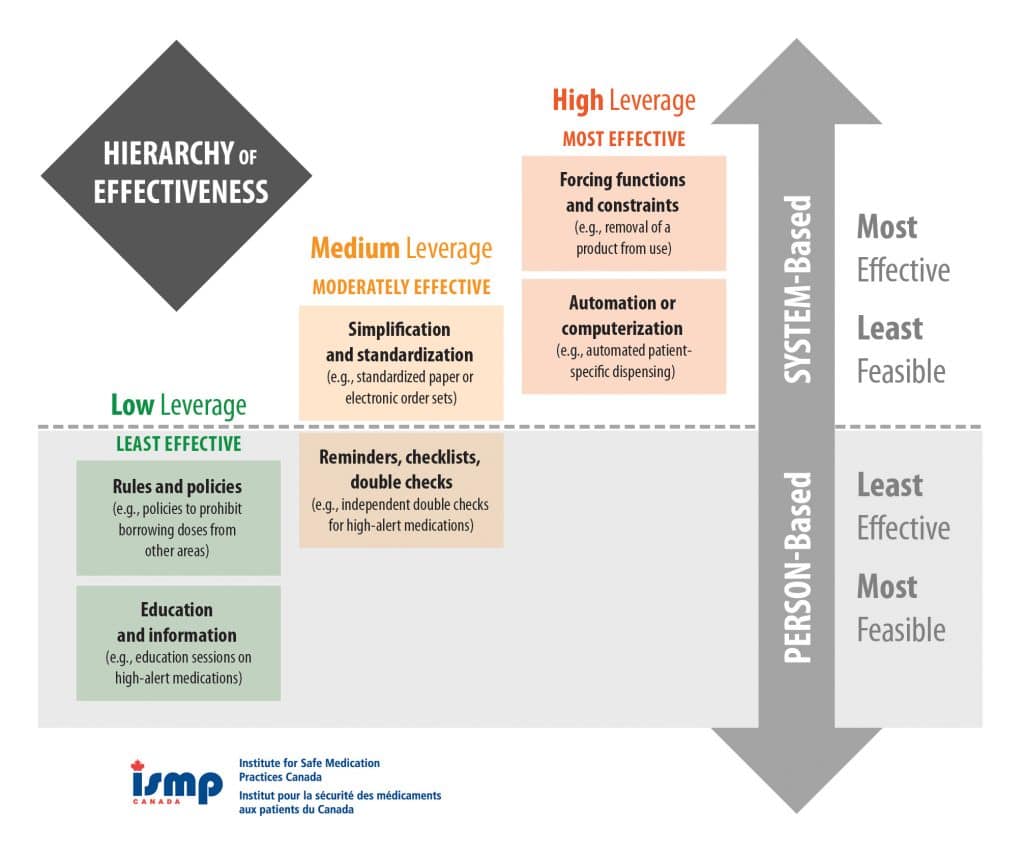

Developing an Improvement Plan using the Hierarchy of Effectiveness

In continuous quality improvement (CQI), it is important to know what changes should be implemented to improve patient safety. ISMP Canada developed the Hierarchy of Effectiveness to help healthcare providers and quality assurance officers make decisions about the type of improvements to make in their practices.

The Hierarchy of Effectiveness differentiates between person-based and system-based changes, and between low, medium, and high leverage changes. System-based changes with high to medium leverage have a greater likelihood of success, but are often difficult to implement. Person-based changes, while important, have a lower chance of success, but are often easier to implement.

Effectiveness differentiates between person-based and system-based changes, and between low, medium, and high leverage changes. System-based changes with high to medium leverage have a greater likelihood of success, but are often difficult to implement. Person-based changes, while important, have a lower chance of success, but are often easier to implement.

Hierarchy of Effectiveness: SYSTEM-Based Approaches

The following system-based changes with high to medium leverage have a greater likelihood of success, but are often difficult to implement.

Forcing Functions and Constraints

Forcing functions and constraints are the most effective error prevention tools because they make it nearly impossible or extremely difficult to make an error. A forced function in a community pharmacy could include a computer system that prevents overriding selected high-alert messages with a notation, or a bar-code scanning system that does not allow final verification of a product without a positive match between selected product and the profiled medication.

Constraints in a community pharmacy involve fundamental system changes in the design of products or systems. For example, at a community pharmacy where the pharmacy computer system is integrated with the cash register, a fail-safe would prevent the clerk from “ringing-up” the prescription unless final verification by a pharmacist was noted.

Automation and Computerization

Automation and computerization of medication-use processes and tasks means that pharmacy staff don’t have to rely exclusively on memory to create a safer system. Examples would include robotic prescription preparation and dispensing systems, or computer software that provides accurate warnings related to allergies, significant drug interactions, and excessive doses.

Simplification and Standardization

Simplification and standardization reduces complexity and brings uniformity to various functions to diminish variation of a specific process. For example, a standardized, documented process for a pharmacist’s final verification of a medication reduces confusion and variation in practice. While simplification and standardization are medium leverage and system-based, they rely on human vigilance and are therefore less effective than forcing functions, constraints, automation, and computerization.

Hierarchy of Effectiveness: PERSON-Based Approaches

Person-based changes, while important, have a lower chance of success, but are often easier to implement.

Reminders, Checklists, and Double Checks

Reminders and checklists can help make important information readily available. Some examples could include using pre-printed prescription blanks that include prompts for critical information such as the indication for the medication, allergies, and the patient’s birthdate.

Independent Double Checks

Having another qualified pharmacy professional verify a calculation or prescription before it reaches the patient increases the odds of catching a near-miss medication incident. When those checks are independent, meaning the second-checker has no previous knowledge of the calculation, they increase the odds even further. For example, an error in drug concentration will be caught more often if the person performing the double check does not see any of the prior calculations.

Rules and Policies

Rules and policies should clearly outline the steps and the expectations of a given process. It is doubly important that there are clear, simple steps and expectations outlined for high-risk processes. For instance, employing a photo identification procedure for selected high-alert medications such as methadone to assist in confirming a patient’s identity and ensuring the correct patient receives the correct medication.

Education and Information

Pharmacy staff are required to possess the knowledge necessary to perform their duties competently and any changes to long-standing procedures require re-education. Patient education also plays a key role in safety. For the photo identification example listed above, the pharmacy can support patient education by placing signs in the pharmacy explaining the identity verification process, why it is needed, and how patients can help by ensuring the verification takes place.

Rules, policies, education and information are the easiest to implement, however, they are the lowest leverage tactics because they rely the most on human vigilance. Success therefore depends on strong ongoing support from pharmacy management to ensure all pharmacy staff comply.

It is up to each individual pharmacy and its staff to design effective tactics for improving patient safety that will best fit their unique needs, workload and environment. When considering changes that are proactive or reactive to medication incident prevention, pharmacy professionals should use the Hierarchy of Effectiveness as a decision-making guide in relation to the benefits and costs each tactic provides.

Sources:

Selecting the Best Error-prevention “Tools” for the Job. Institute for Safe Medication Practices. <https://www.ismp.org/newsletters/ambulatory/archives/200602_4.asp.> Accessed September 8, 2017.

Canadian Failure Mode and Effects Analysis Framework: Proactively Assessing Risk in Healthcare, Version III. Institute for Safe Medication Practices Canada, Toronto, ON, 2017.

Evaluating Changes using Plan, Do, Study, Act

To ensure that the improvement and action plans you implemented are effective, your team needs to monitor and evaluate them. The Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycle can be used to test change(s) to determine if the were successful. The PDSA cycle is a short hand for testing change in your work setting by planning changes, trying them out, observing the results, and acting on what is learned. This is a scientific method adapted for action-oriented learning.

You can also use PDSA cycles to test a change quickly on a small scale, see how it works, and refine the change as necessary before implementing it on a broader scale. The following example shows how a team started with a small-scale test.

Plan: After analysis of the incident, the pharmacy team decides on changes they want to implement to reduce the chance of recurrence of a medication incident or near-miss event.

Your team must clearly define specific measurable and time-bound goals. For example, ‘we will reduce look-alike, sound-alike errors and/or near-misses by 75 per cent in the next three months.’

Do: Outline when and how the changes will be implemented. Communicate changes with your team and put them into action.

Study: What were the results? Track changes over time to determine if your change resulted in the expected outcome.

Act: Based on your study of the changes, do you need to modify your changes to achieve a better result? Modify your plan as needed and begin the PDSA cycle again.

Diabetes: Planned visits for blood sugar management (PDSA Example)

Plan: Ask one patient if he or she would like more information on how to manage his or her blood sugar.

Do: Pharmacist B asked his first patient with diabetes on Tuesday.

Study: Patient was interested; Pharmacist B was pleased at the positive response.

Act: Pharmacist B will continue with the next five patients and set up a planned visit for those who say yes.

What is a SMART objective?

SMART objectives are statements of action that describe what you need to accomplish in order to meet your goal(s). SMART stands for:

Specific – It describes a specific action, behaviour, outcome or achievement that is observable.

Measurable – It is quantifiable and has indicators associated with it so it can be measured.

Achievable – It is feasible with the available resources.

Relevant – It is tied to overall goals or organizational direction.

Time-Bound – It states the time-frame within which the objective will be achieved.

Why should we create SMART Objectives?

Creating SMART objectives will give your team a structure to achieve your quality improvement goals. The SMART objective approach allows your team to create, measure, and accomplish short and long-term goals providing you with a road map or path to what you want to achieve. When goals are vague or unmeasurable, they are less likely to succeed or make meaningful change.

What Resources are Available for SMART objectives in community pharmacy?

The Institute for Safe Medication Practices Canada created SMART Medication Safety Agendas to provide pharmacy teams with an improvement framework using real-life case studies and data they receive about medication incidents and near-miss events in Canada. A listing of the SMART Medication Safety Agendas is available at the following link: https://cphm.ca/practice-education/shared-learning/

Tips for writing SMART objectives

Specific

- Formulate the objective in concrete, detailed, and well-defined terms so that expectations are clear.

- Describe the objective using strong action verbs, such as “conduct,” “develop,” “build,” “plan,” or “execute.”

- Avoid using verbs that may have vague meanings (e.g., “understand” or “know”) since the objective may then prove difficult to measure.

Measurable

- Focus the objective on “how much” change is expected, ideally in quantifiable terms.

- A measurable goal should address questions such as:

- How much?

- How many?

- How will I know when it is accomplished?

Achievable

- Make sure that objectives can be feasibly implemented given various constraints, including resources, personnel, cost, and timeframe.

Relevant

- An effective objective should be relevant to what the organisation and/or the team wants to achieve.

- Objectives should answer the following questions

- Why are we setting this goal now?

- Is this goal aligned with our overall objectives?

Time-Bound

- Include a timeframe indicating when the objective will be measured or a time by which the objective will be met.

Example

“In alignment with the pharmacy’s overall goal to reduce the chance of patient harm, our team will reduce look-alike, sound-alike medication incidents and/or near-miss in events by 60 percent in three months.”

What is Continuous Quality Improvement?

Continuous quality improvement (CQI) is an ongoing approach to problem-solving and harm prevention. CQI focuses on identifying the root causes of a problem and introducing ways to eliminate or reduce the problem through open-ended analysis and assessment of process change.

In the pharmacy field, CQI focuses on preventing medication incidents and continually looking for ways to improve medication dispensing, therapy management, and counselling.

How do we choose what to work on?

CQI involves taking the additional steps beyond reporting to analyze how and why an incident occurred and searching for solutions to prevent recurrence. You look for contributing factors and root causes to develop changes in systems and processes rather than simply asking the pharmacy staff to try harder.

Effective CQI requires a team approach as each staff member will have a different perspective on the problem, contributing factors, and ideas for solutions. CQI is an ongoing process and the necessary CQI skills evolve over time with education and practice. Many tools are available to assist with analysis; however, it may be best to start with a simple process then move onto others tools as you and your team become more confident and knowledgeable.

Your team should always be specific about improvement goals. Your goals should be measurable and time-bound. For example, ‘we will reduce look-alike, sound-alike medication errors and/or near-misses by 50 per cent over the next three months.’

What is a contributing factor?

A contributing factor is a circumstance, action, or influence which is thought to have played a part in the origin or development of an incident or near-miss, or to increase the risk of an incident or near-miss.

What is a root cause?

A root cause is the most fundamental reason (or one of several fundamental reasons) a suspected failure such as a medication incident or near-miss has occurred.